Mechanical Engineering and Engineering Science

Mechanical engineering studies leading to a bachelor’s of science degree at UNC Charlotte got their start in 1965, when the university hired its first mechanical engineering faculty members, Walt Norem and Rhyn Kim. In its earliest days, the program was known as Engineering Science, Mechanics and Materials.

A faculty member in the program for more than 30 years, Yogi Hari actually began his career in the Lee College of Engineering in the Engineering Analysis and Design (later Electrical Engineering) program. An expert in the field of machine design, Hari came to UNC Charlotte in 1978. Machine design involved electronic controls and systems, as well as mechanics, so Hari was comfortable teaching, consulting and performing research in both the electrical and mechanical engineering. In 1983, he transferred the Mechanical Engineering and Engineering Science Department.

Hari came to the United States in 1962, where he earned his masters and Ph.D. at Purdue University. For the next 15 years, he worked in industry, taught at several universities and was self-employed. His industrial specialization was mechatronics, the multidisciplinary field of mechanical, electrical and systems engineering. Companies he worked at and consulted with included National Cash Register, Celanese, Duke Cogema, Stone & Webster, Investa and Metso Power. Universities he taught at included Gannon, the Indiana Institute of Technology and North Carolina A&T.

Much of Hari’s work included developing analytical systems to help design and perform quality assessment of machines. He also worked on transformers, pressure vessels, piping and storage tanks for nuclear facilities. He decided to go to work at UNC Charlotte in order to put down roots in one place.

“I wanted to get back into teaching full-time,” Hari said. “I did, and through all the ups and downs, I was here for 37 years.”

Hari said he was a tough professor, especially at the beginning of his career. To help students learn difficult engineering subjects, he developed 50 work books. “They are all on Amazon, and all sell for $9.99,” he said. He also developed solutions manuals for machine design textbooks, which took students though each problem step by step.

In his first years at UNC Charlotte, Hari continued a lot of his consulting work. “Dean Snyder very much encouraged consulting,” he said. “We didn’t have much research at the time.”

A big step for the Lee College of Engineering in both academics and research was the start of the master’s program in 1979. “When we started the master’s program, we then had more resources to help with research,” Hari said. During his career, he graduated 38 master’s students and two Ph.D. students.

Research also increases with the building of the Cameron Applied Research Center in 1991. One group in the new building that was especially important to mechanical engineering was precision engineering and metrology, which was led by Bob Hocken.

“I worked on coordinate measuring machines with Bob Hocken,” Hari said. “A lot of my research was writing software for CMM measurement systems.”

Hari retired from UNC Charlotte in 2010 and the university granted him emeritus status in 2011.

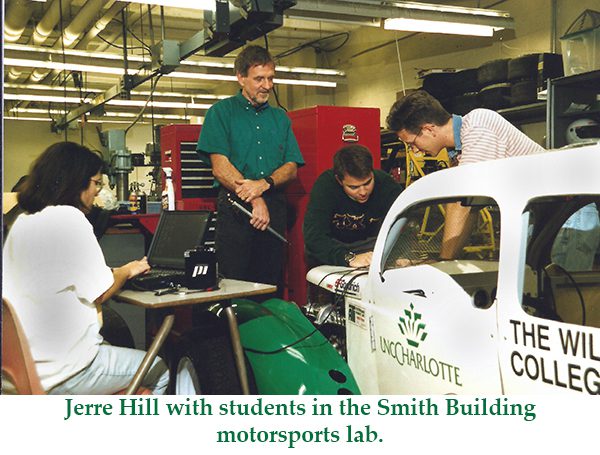

Jerre Hill started his mechanical engineering career at UNC Charlotte in the summer of 1986. He earned his Ph.D. from Virginia Tech in 1983, and then on the advice of one of his professors had gone to work in the private sector, taking a job at Pratt & Whitney Aircraft in West Palm Beach, Florida.

“It was really good advice for me get post-doctoral industrial experience,” Hill said. “Many times during the course of my teaching career my students commented that they enjoyed my stories from industry about the application of what we were learning.”

When Hill decided to return to academia, his wife had just been transferred to IBM in Charlotte, so he went to UNC Charlotte looking for a teaching position. “I came here to meet Paul DeHoff (chair of Mechanical Engineering at the time),” Hill said. “I went in and introduced myself and told him I had just moved up here. I told him about my teaching experience and he said ‘alright, we can use you.’ And he hired me on the spot.”

DeHoff hired Hill on a year-to-year contract. To make himself more valuable, Hill decided to teach as many classes as possible. “I was a thermal science guy,” he said, “but I started teaching everything under the sun, including statics, dynamics I and II, and stuff you wouldn’t think I’d be doing. I guess it worked. Back then I knew all the students. I was the only person teaching thermal II, so every single student had to come though me.”

Hill stayed at UNC Charlotte for the next 30 years, winning five teaching awards along the way. “I liked the Charlotte area, I liked the school and I loved to teach,” he said. “Every year I had a couple students come in and shake my hand and thank me for being a role model. Even ones I had no idea I was having such an impact on. It was kind of humbling for me when students came and told me what a big impact I had on their lives. It really made it worthwhile. How many jobs can you have where you get to influence so many people? I loved this job.”

An expert in the field of surface metrology, Jay Raja collaborated with some the discipline’s leader researchers in places including India, London, Germany and the United States. “It was a small community, and I was fortunate to work with some of top people in the field,” Raja said. “While I was doing a post-doc fellowship in London I came to know about Hocken.”

Raja took a position at Michigan Tech and while there was able to spend summers doing research at the National Institute of Standards and Technology with Hocken. “When Hocken came to UNC Charlotte,” Raja said, “I was pretty settled in Michigan. But there was an opportunity here to set up a research center in metrology. That’s what brought me here.”

The idea of being part of a group of researchers dedicated to precision engineering and metrology research was appealing to Raja, as was the chance to build a new program. “I was intrigued by the challenge of going to a school that wanted to get things started,” he said, “instead of one that already had them established. It was a time I thoroughly enjoyed.”

The precision program was very successful in its research and also in the education of future precision engineers. “The biggest contribution of the program was producing the next generation of leadership in metrology,” Raja said. “We did a great job attracting, training and letting loose people who continued to practice metrology and help industry. I felt one of my greatest contribution was the 25 masters and 11 Ph.D. students I graduated.”

Raja became chair of Mechanical Engineering in 2000. His tenure was during a period of huge growth in the program, as undergraduate enrollment went from 260 when he started to 800 when he left eight years later.

“It was a period of rapid growth,” Raja said, “and I was fortunate to be able to help recruit 15 faculty members. I always enjoyed recruiting people and telling them about the campus and our program. My line I used to tell candidates was that you can go to a campus that will lend you its name, or you can come here and make a name for yourself.”

Raja was also involved in the planning and establishment of Duke Centennial Hall and the new motorsports buildings. “Working on the new buildings was fun for me. I was part of the design team, along with plenty of others, who designed the Duke building. We were able to create a really terrific infrastructure here. I would say we have the best engineering buildings of any college I know. Others may have more square footage, but we have been able to move into new space designed specifically for engineering study and research.”

In 2008, Raja left Mechanical Engineering to become senior associate provost for UNC Charlotte. He transferred his commitment and dedication to helping students succeed from the department to the university level.

“We were a very special institution,” Raja said. “We were selective, but not highly selective. We had a special mission to train students who had the capability for academic success. It was our task to help them develop in to full-fledged graduates. As a faculty member, you didn’t set out to change anybody’s life, you were just doing your job, teaching and research. But in end, it seems like you did make a small difference in students’ lives.”

Harish Cherukuri came to the Mechanical Engineering Department as a post-doc student in 1995, and then joined the faculty in 1997. He came from the University of Illinois, where he had known Bob Johnson. Cherukuri’s area of expertise was solid mechanics and computational mechanics.

“At that time, the research culture here was just beginning to become established,” Cherukuri said. “What I liked about moving to Charlotte and our university was the balance between teaching and research. Teaching was considered just as important as research, and I really liked that. The second thing I liked about the place was the department atmosphere was so positive. The department was growing and I thought it was a dynamic environment.”

The amount of change and growth in the department was astounding during Cherukuri’s career. “We had about 15 to 20 Ph.D. students, and by 2014 it was 55 to 60,” he said. “Back in ’94, the department from the research point of view was just metrology and precision engineering. Then it added biomedical engineering, motorsports and computation mechanics. The increased options helped attract more students.”

What remained the same during all of the growth of enrollment, programs and facilities was the dedication to delivering quality education to the students, Cherukuri said. “The commitment of a balance between teaching and research stayed the same. I got the opportunity to grow at a professional level, and got the opportunity to teach the courses I liked to teach. The atmosphere was always positive.”

For the future, Cherukuri said mechanical engineering will begin to incorporate elements of other engineering disciplines such as electrical, as students learn about subjects such as controls, robotics and automotive engineering. There will also be new undergraduate offerings in biomedical engineering, mixing mechanical engineering with components of biology and chemistry.

“This was a great place to be,” Cherukuri said. “Even as we changed, and will continue to change, the mood was always very positive. The faculty were, and still are, great to work with as colleagues. This is still a great place to be.”

An expert in machine tools, Scott Smith first came to UNC Charlotte on sabbatical leave from the University of Florida in 1996. “I was up for a sabbatical,” he said. “I asked around as to where I should go and everybody said ‘You should go work with Hocken.’ I said ‘Where’s that?’ They said ‘UNC Charlotte.’ I said ‘where’s that? I thought I was going to be here for nine month. Nineteen years later I was still here.”

Smith started the machining research program within the Center for Precision Metrology. Up until his coming to UNC Charlotte, most of the group’s machining work involved measuring the motions of machine tools, but not making things with the high-speed tools. The research area continued to grow, with the addition of Matt Davies, Tony Schmitz, John Ziegert and Chris Evans.

“We grew the capability to do everything from polishing to making aerospace parts and optical components,” Smith said. “We were a little bit like a startup company. There was not enough money, not enough resources, everybody had to do everything, but the potential was amazing. So, if you liked program building, it was a really good place to be.”

When Jay Raja left the position as chair of mechanical engineering, Robin Coger first filled in as interim chair, and then Smith was hired as permanent chair in 2008. He considered himself fortunate to be taking over a program that was growing and had fantastic new facilities in Duke Hall to support its growth.

“The facilities were outstanding,” Smith said. “Certainly in a university environment they were the best in the country. Many major research universities, when they talk about their new facilities, they mean the ones built after World War II.”

For the motorsports program, the new Kulwicki Laboratory and then later in 2012 the new Motorsports Research Building provided the space for undergraduate project race teams and graduate and faculty research.

Undergraduate and graduate mechanical engineering enrollment continued to increase, topping 1,000 total students in 2014. “The rate of growth was amazing,” Smith said. “The Department of Mechanical Engineering was bigger in 2015 than the whole college was when I started here.”

Much of the growth in mechanical engineering enrollment was the result of North Carolina demographics, with more people moving to the region. “I think our growth was also due to the quality of the program,” Smith said. “The design-and-build nature of the program was very valuable. Our students left us with jobs and they left us with good jobs. It was obvious that attracted them.”

There were difficulties coping with the high rate of growth at a time when the state budget was tight. “It was a real tribute to the faculty that we continued to deliver such a high-quality program,” Smith said.

One strategy for dealing with the growth and making better use of facilities was to increase the number of classes offered during summer semesters. “Nearly everything that was required for the degree was offered in the summer,” Smith said. “That was good. We got to the stage where summer just looked like another semester for us. That was better use of the facilities.”

In the undergraduate program, mechanical engineering began offering concentrations in energy and then in bioengineering, in addition to the traditional motorsports concentration. The energy concentration was a direct result of the university’s new EPIC program.

“In the local power industry,” Smith said, “70 percent of the engineers hired were local. We had a lot of students who came into the program already knowing they wanted to work for Duke or Siemens or some other company in the power industry. So, the energy concentration was a very attractive option for them.”

The creation of EPIC brought with it a number of new faculty positions, some of which were in mechanical engineering. “EPIC allowed us to make hires we wouldn’t have been able to otherwise,” Smith said. “It also deepened our research connections with area energy companies and it increased the visibility of our students to those companies.”

In the future, Smith said he expected to see a new concentration in precision engineering. He also expected more growth in the graduate program, especially in the area of non-thesis master’s degree programs. Whatever changes did happen would be grounded in the department’s traditional foundation of hands-on, applied education and research.

“I told people who came here that design-and-build was woven all through our programs,” Smith said. “The hands-on augmented the theoretical, not only in the classroom where students were learning things, but also in the labs and shops where they were measuring things, designing things and building things. It was a very valuable combination. The students liked it and the employers liked it.”

During his 19 years at UNC Charlotte, it was the program-building aspects of his job that were the most rewarding, Smith said. “It was exciting to be in a growth environment. It was good to be able to spend some time thinking about what might be possible and then be able to execute it. If you had asked me how the Mechanical Engineering Department could look when I first came here, even in my wildest estimate I would have under-guessed where we got to. And I think the potential is still quite strong to go much further.”